We leverage open-source resources and tools to teach students valuable tech skills. The resources are continually updated and refined by developers around the world, ensuring our students learn with the most current, widely-used technologies.

Mobile Development Curriculum (12 Months)

This unit introduces Kotlin and how to set up the development environment for Android development.

What is Kotlin?

Kotlin is a modern, trending programming language that was released in 2016 by JetBrains.

It has become very popular since it is compatible with Java (one of the most popular programming languages out there), which means that Java code (and libraries) can be used in Kotlin programs.

Kotlin is used for:

- Mobile applications (especially Android apps)

- Web development

- Server-side applications

- Data science

- And much more!

Why Use Kotlin?

- ✅ Fully compatible with Java

- ✅ Works on different platforms (Windows, Mac, Linux, Raspberry Pi, etc.)

- ✅ Concise and safe

- ✅ Easy to learn, especially if you already know Java

- ✅ Free to use

- ✅ Big community/support

Get Started

This tutorial will teach you the very basics of Kotlin.

It is not necessary to have any prior programming experience.

Kotlin IDE

The easiest way to get started with Kotlin is by using an IDE (Integrated Development Environment).

An IDE is used to edit and compile code efficiently.

For this guide, we will use IntelliJ IDEA, developed by the same creators of Kotlin. It is free to download from:

Kotlin Install

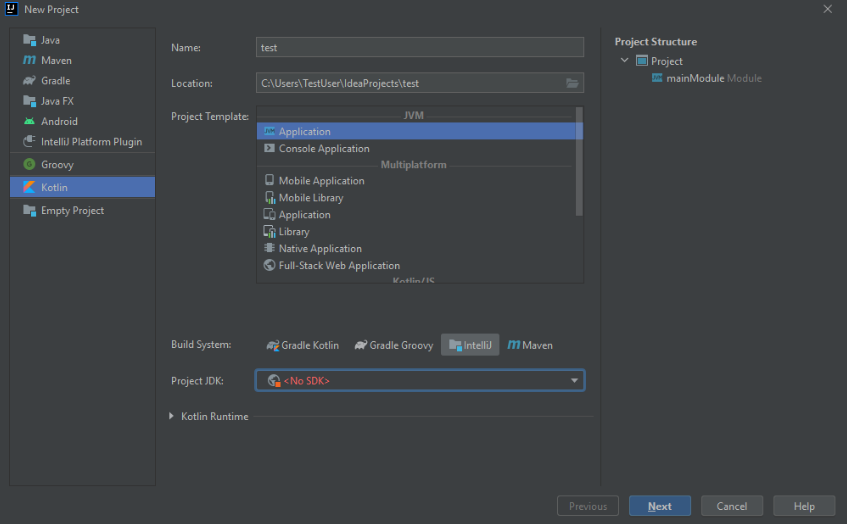

Once IntelliJ is downloaded and installed, click on the New Project button to get started:

Then, click on "Kotlin" in the left-side menu and enter a name for your project:

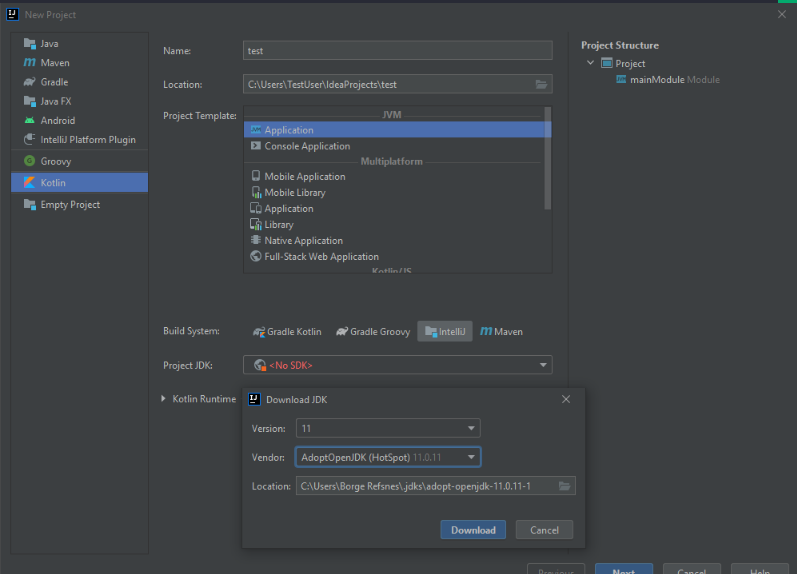

Next, we need to install the JDK (Java Development Kit) to run Kotlin projects. Click on the "Project JDK" menu, select "Download JDK", then choose a version and vendor (e.g., AdoptOpenJDK 11), and click "Download":

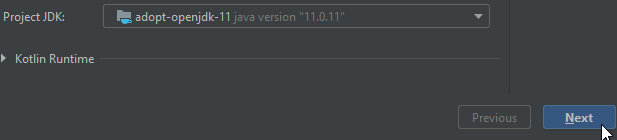

When the JDK is installed, select it from the menu and click "Next", then "Finish":

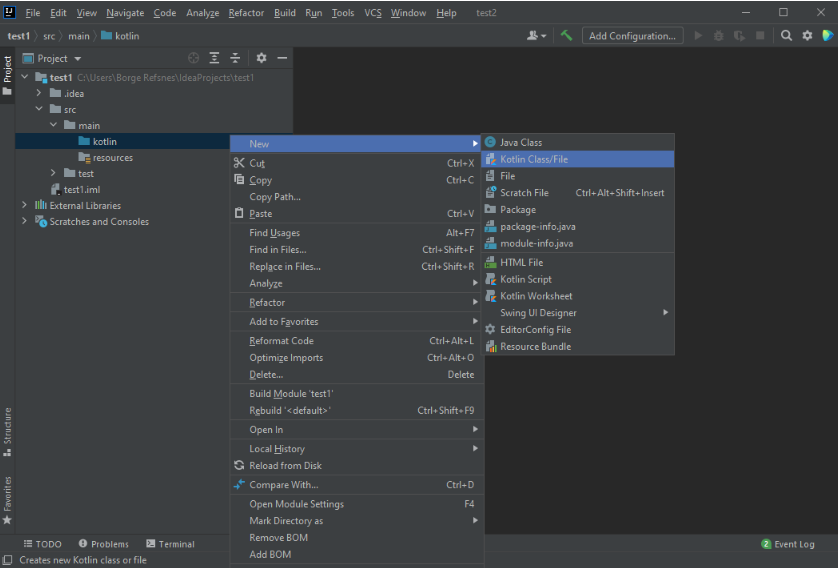

Now, let's start working with Kotlin! Open the src (source) folder and follow the steps in the image below to create a new Kotlin file:

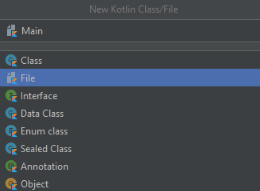

Choose "File", enter a name for your Kotlin file (e.g.,

Main):

Kotlin Syntax

In the previous chapter, we created a Kotlin file called Main.kt, and we used the following

code to print "Hello World" to the screen:

Example

fun main() {

println("Hello World")

}Example Explained

The fun keyword is used to declare a function. A function is a block of

code designed

to perform a particular task.

In the example above, we declared the main() function, which is the entry point of every

Kotlin program.

Any code inside the main() function's curly brackets { } will be executed.

The println() function is inside main(), meaning that it will be executed.

The println() function is used to output/print text, and in our example, it will output:

Output:

Hello World📌 Good to Know:

In Kotlin, **statements do not require a semicolon** (;) at the end, unlike Java, C++, or

C#.

However, if you place multiple statements on the same line, you **must** use a semicolon to separate them:

Example:

fun main() { println("Hello"); println("World") }Output:

Hello

WorldMain Function Parameters

Before Kotlin version **1.3**, the main() function was required to have parameters.

The correct syntax was:

Example:

fun main(args: Array) {

println("Hello World")

} However, starting from Kotlin 1.3, **parameters are optional**, and the program will run fine without them.

✅ Modern Syntax (No Parameters Required)

fun main() {

println("Hello World")

}Even though parameters are no longer required, you can still use them if needed. For example, you can access command-line arguments like this:

Example:

fun main(args: Array) {

if (args.isNotEmpty()) {

println("Command-line argument: " + args[0])

} else {

println("No arguments provided.")

}

} If you run the program with an argument (e.g., Hello Kotlin), the output will be:

Output:

Command-line argument: Hello KotlinTry it Yourself

Want to experiment with Kotlin code? Use the Try it yourself Tool to test the examples online.

🎉 Now that you understand Kotlin syntax, let's move on to writing more advanced Kotlin programs!

Kotlin Output (Print)

The println() function is used to output values or print text in Kotlin.

Example:

fun main() {

println("Hello World")

}Output:

Hello WorldPrinting Multiple Lines

You can use multiple println() functions to print text on separate lines.

Example:

fun main() {

println("Hello World!")

println("I am learning Kotlin.")

println("It is awesome!")

}Output:

Hello World!

I am learning Kotlin.

It is awesome!Printing Numbers and Calculations

Kotlin allows you to print numbers and perform mathematical operations directly inside

println().

Example:

fun main() {

println(3 + 3)

}Output:

6The print() Function

The print() function is similar to println(), but it does not insert a

new line at the end of the output.

Example:

fun main() {

print("Hello World! ")

print("I am learning Kotlin. ")

print("It is awesome!")

}Output:

Hello World! I am learning Kotlin. It is awesome!💡 Notice how all the text is printed on the same line.

Comparing println() vs. print()

| Function | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

println() |

Prints text and moves to a new line | println("Hello") |

print() |

Prints text on the same line | print("Hello") |

Try it Yourself

Want to test your Kotlin code? Use the Try it yourself Tool to practice printing output in Kotlin.

🎉 Now that you understand how to print text and numbers in Kotlin, let's move on to working with **variables**! 🚀

Kotlin Comments

Comments are used to **document** code, make it more **readable**, and prevent execution when testing alternative code.

There are **two types** of comments in Kotlin:

- Single-line comments (Using

//) - Multi-line comments (Using

/* */)

Single-line Comments

Single-line comments start with **two forward slashes (`//`)**.

Any text after // on the same line is **ignored by Kotlin** (will not be executed).

Example: Single-line comment before a line of code

// This is a comment

println("Hello World")Example: Single-line comment at the end of a line

println("Hello World") // This is a commentOutput:

Hello World💡 The comment does not affect the execution of the code.

Multi-line Comments

Multi-line comments start with /* and end with */.

Everything inside /* ... */ will be **ignored** by the compiler.

Example: Multi-line comment (Block comment)

/* The code below will print the words "Hello World"

to the screen, and it is amazing */

println("Hello World")Output:

Hello WorldUsing Comments to Disable Code

Developers often **disable code** by turning it into a comment:

Example:

// println("This line will not run")

println("Hello Kotlin!")Output:

Hello Kotlin!💡 The first line is ignored because it is a **comment**.

Why Use Comments?

- 📝 **Explain complex code** to make it more readable.

- 🛠 **Disable lines of code** during testing.

- 👥 **Help teams understand the purpose of the code**.

Try it Yourself

Want to experiment with Kotlin comments? Use the Try it yourself Tool to test the examples online.

🎉 Now that you understand Kotlin comments, let's move on to **Kotlin Variables!** 🚀

This unit introduces **Kotlin Variables**, how to declare them, their types, and best practices.

Kotlin Variables

Variables are containers for storing data values.

To create a variable, use var or val, and assign a value using

the = sign.

Syntax:

var variableName = value

val variableName = valueExample:

var name = "John"

val birthYear = 1975

println(name) // Output: John

println(birthYear) // Output: 1975Difference Between var and val

var: Variables **declared with `var` can be changed/modified**.val: Variables **declared with `val` cannot be changed** (like constants).

Example:

var name = "Alice"

name = "Bob" // This works because 'name' is declared with 'var'

val pi = 3.14159

pi = 3.14 // Error! 'val' variables cannot be changedVariable Type

Kotlin **does not require specifying variable types** (e.g., `String`, `Int`), because it can infer them automatically.

Example:

var name = "John" // String

val birthYear = 1975 // Int

println(name) // Output: John

println(birthYear) // Output: 1975However, you can **specify the type explicitly** if needed.

Example:

var name: String = "John"

val birthYear: Int = 1975

println(name)

println(birthYear)Declaring a Variable Without Assigning a Value

You **must specify the type** if you declare a variable without assigning a value.

✅ This works fine:

var name: String

name = "John"

println(name)❌ This will generate an error:

var name

name = "John"

println(name) // ERROR! Kotlin does not know the type of 'name'💡 You will learn more about **Data Types** in the next chapter.

Notes on val

Variables created with **`val` cannot be reassigned** after they are initialized.

❌ This will generate an error:

val name = "John"

name = "Robert" // Error: Val cannot be reassigned

println(name)✅ Using var allows reassignment:

var name = "John"

name = "Robert"

println(name) // Output: RobertWhen to Use val?

The **`val` keyword** is useful when you want a variable to always store the same value, like PI.

Example:

val pi = 3.14159265359

println(pi) // Output: 3.14159265359Displaying Variables

You can display variables using println().

Example: Printing a Variable

val name = "John"

println("Hello " + name)Output:

Hello JohnYou can also **combine two variables using `+`**.

Example:

val firstName = "John "

val lastName = "Doe"

val fullName = firstName + lastName

println(fullName) // Output: John DoeFor numbers, `+` acts as a mathematical operator:

Example:

val x = 5

val y = 6

println(x + y) // Output: 11Variable Naming Rules

Variable names can contain:

- Letters (A-Z, a-z)

- Digits (0-9)

- Underscores

_ - Dollar signs

$(Not recommended)

Variable Naming Conventions

- ✅ **Must start with a letter** (e.g., `age`, `totalPrice`)

- ✅ Can **contain numbers** but cannot start with them (e.g., `score1`, `userCount`)

- ✅ **Case-sensitive** (`myVar` and `myvar` are different)

- ✅ Should **start with a lowercase letter** and **cannot contain spaces**

- ❌ **Reserved words** (e.g., `var`, `String`) **cannot be used as variable names**

CamelCase Variable Names

By convention, Kotlin uses **camelCase** for variable names.

Examples:

var firstName = "John" // ✅ Good practice

var lastName = "Doe"

var myAge = 25⚠️ Avoid writing variables like `firstname` or `lastname`. CamelCase improves readability.

Try it Yourself

Want to experiment with Kotlin variables? Use the Try it yourself Tool to practice variables in Kotlin.

🎉 Now that you understand Kotlin variables, let's move on to **Data Types!** 🚀

Kotlin Data Types

In Kotlin, the type of a variable is determined by its value:

Example:

val myNum = 5 // Int

val myDoubleNum = 5.99 // Double

val myLetter = 'D' // Char

val myBoolean = true // Boolean

val myText = "Hello" // StringHowever, you can also **explicitly specify the type**:

Example:

val myNum: Int = 5

val myDoubleNum: Double = 5.99

val myLetter: Char = 'D'

val myBoolean: Boolean = true

val myText: String = "Hello"Kotlin will automatically determine the type in most cases, but sometimes you **must specify it explicitly**.

Types of Data in Kotlin

- 🔢 **Numbers** - Integers, Floating points

- 🔠 **Characters** - Single character values

- ✅ **Booleans** - `true` or `false`

- 📝 **Strings** - A sequence of characters

- 📦 **Arrays** - A collection of values

Numbers in Kotlin

Numbers in Kotlin are categorized into **Integer Types** and **Floating Point Types**.

📌 Integer Types

| Type | Size | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Byte | 8-bit | -128 to 127 |

| Short | 16-bit | -32,768 to 32,767 |

| Int | 32-bit | -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647 |

| Long | 64-bit | -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 |

Examples:

val myByte: Byte = 100

val myShort: Short = 5000

val myInt: Int = 100000

val myLong: Long = 15000000000L💡 Long values should end with **"L"** to differentiate them from Int.

📌 Floating Point Types

| Type | Size | Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Float | 32-bit | 6-7 decimal places |

| Double | 64-bit | 15 decimal places |

Examples:

val myFloat: Float = 5.75F

val myDouble: Double = 19.99💡 **Use "F" at the end** of Float values to differentiate them from Double.

Scientific Notation

Floating point numbers can be written using **scientific notation**:

Example:

val myNum1: Float = 35E3F

val myNum2: Double = 12E4

println(myNum1) // Output: 35000.0

println(myNum2) // Output: 120000.0Booleans

The **Boolean** data type can hold only two values: `true` or `false`.

Example:

val isKotlinFun: Boolean = true

val isFishTasty: Boolean = false

println(isKotlinFun) // Output: true

println(isFishTasty) // Output: falseCharacters

The **Char** data type stores **single characters** and must be enclosed in **single quotes** (`'A'`).

Example:

val myGrade: Char = 'B'

println(myGrade) // Output: B⚠️ **You cannot use ASCII values** to assign characters in Kotlin:

❌ Incorrect Example:

val myLetter: Char = 66

println(myLetter) // ErrorStrings

The **String** data type is used to store a sequence of characters.

Example:

val myText: String = "Hello World"

println(myText)Arrays

Arrays store **multiple values** in a **single variable**.

💡 You will learn more about Arrays in the Arrays chapter.

Type Conversion

In Kotlin, you **must use conversion functions** to change a numeric type to another type.

❌ Incorrect Example:

val x: Int = 5

val y: Long = x // Error! Type mismatch✅ Correct Example:

val x: Int = 5

val y: Long = x.toLong()

println(y) // Output: 5Try it Yourself

Want to experiment with Kotlin Data Types? Use the Try it yourself Tool to practice.

🎉 Now that you understand Kotlin Data Types, let's move on to **Arrays!** 🚀

Kotlin Operators

Operators are used to perform operations on variables and values.

In an operation:

- The values are called operands.

- The symbol that performs the operation is called an operator.

Example:

In the operation below, 100 and 50 are operands, and + is the

operator:

var x = 100 + 50You can also add variables and values together:

Example:

var sum1 = 100 + 50 // 150 (100 + 50)

var sum2 = sum1 + 250 // 400 (150 + 250)

var sum3 = sum2 + sum2 // 800 (400 + 400)Types of Kotlin Operators

Kotlin operators are categorized into the following groups:

- Arithmetic Operators

- Assignment Operators

- Comparison Operators

- Logical Operators

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators perform mathematical operations.

| Operator | Name | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

+ |

Addition | Adds two values | x + y |

- |

Subtraction | Subtracts one value from another | x - y |

* |

Multiplication | Multiplies two values | x * y |

/ |

Division | Divides one value by another | x / y |

% |

Modulus | Returns the division remainder | x % y |

Example:

var a = 10

var b = 5

println(a + b) // Output: 15

println(a - b) // Output: 5

println(a * b) // Output: 50

println(a / b) // Output: 2

println(a % b) // Output: 0Assignment Operators

Assignment operators assign values to variables.

| Operator | Example | Same As |

|---|---|---|

= |

x = 5 |

x = 5 |

+= |

x += 3 |

x = x + 3 |

-= |

x -= 3 |

x = x - 3 |

*= |

x *= 3 |

x = x * 3 |

/= |

x /= 3 |

x = x / 3 |

Example:

var x = 10

x += 5 // x = x + 5

println(x) // Output: 15Comparison Operators

Comparison operators compare two values and return true or false.

| Operator | Name | Example |

|---|---|---|

== |

Equal to | x == y |

!= |

Not equal | x != y |

> |

Greater than | x > y |

< |

Less than | x < y |

Logical Operators

Logical operators determine the logic between variables or values.

| Operator | Name | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

&& |

Logical AND | Returns true if both conditions are true | x < 5 && x < 10 |

|| |

Logical OR | Returns true if at least one condition is true | x < 5 || x < 4 |

🎉 Now that you understand Kotlin Operators, let's move on to strings! 🚀

Kotlin Strings

Strings are used for storing text.

A string contains a collection of characters surrounded by **double quotes**:

Example:

var greeting = "Hello"Unlike Java, you do **not** have to specify that the variable should be a String. Kotlin is smart enough to understand that the greeting variable in the example above is a String because of the double quotes.

However, just like with other data types, you can specify the type if you want:

Example:

var greeting: String = "Hello"Declaring a String Without an Initial Value

If you want to create a String **without assigning the value** (and assign the value later), you must specify the type while declaring the variable:

✅ This works fine:

var name: String

name = "John"

println(name)❌ This will generate an error:

var name

name = "John"

println(name)Accessing Characters in a String

To access the characters (elements) of a string, you must refer to the **index number** inside square brackets.

String indexes start with 0. In the example below, we access the **first and third** elements in

txt:

Example:

var txt = "Hello World"

println(txt[0]) // First element (H)

println(txt[2]) // Third element (l)Note: Index [0] is the first element, [1] is the second element,

[2] is the third element, and so on.

Finding the Length of a String

A **String** in Kotlin is an **object**, which contains properties and functions that can perform certain operations on strings.

For example, the **length** of a string can be found using the length property:

Example:

var txt = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ"

println("The length of the txt string is: " + txt.length)String Functions

There are many built-in **string functions**, such as toUpperCase() and

toLowerCase():

Example:

var txt = "Hello World"

println(txt.toUpperCase()) // Outputs "HELLO WORLD"

println(txt.toLowerCase()) // Outputs "hello world"Comparing Strings

The **compareTo(string)** function compares two strings and returns 0 if both are equal:

Example:

var txt1 = "Hello World"

var txt2 = "Hello World"

println(txt1.compareTo(txt2)) // Outputs 0 (they are equal)Finding a String in a String

The indexOf() function returns the **index (position)** of the first occurrence of a

specified text in a string.

Example:

var txt = "Please locate where 'locate' occurs!"

println(txt.indexOf("locate")) // Outputs 7Note: Kotlin counts positions from **zero (0)**.

Quotes Inside a String

To use **quotes inside a string**, use single quotes ('):

Example:

var txt1 = "It's alright"

var txt2 = "That's great"String Concatenation

The + operator can be used between **strings** to **add them together**. This is called

**concatenation**:

Example:

var firstName = "John"

var lastName = "Doe"

println(firstName + " " + lastName)Note: We added an empty string " " to create a **space** between

firstName and lastName.

You can also use the plus() function:

Example:

var firstName = "John "

var lastName = "Doe"

println(firstName.plus(lastName))String Templates (String Interpolation)

Instead of concatenation, you can also use **"string templates"**, which is an easier way to add variables and expressions inside a string.

Just refer to the variable with the **$ symbol**:

Example:

var firstName = "John"

var lastName = "Doe"

println("My name is $firstName $lastName")Why Use String Templates?

- ✅ Reduces the amount of code.

- ✅ No need to specify spaces manually (unlike concatenation).

- ✅ Easier to read and maintain.

Kotlin Booleans

In programming, you often need a data type that can have only two possible values, such as:

- YES / NO

- ON / OFF

- TRUE / FALSE

For this, Kotlin provides a Boolean data type, which can take only two values: true

or false.

Boolean Values

A Boolean variable can be declared using the Boolean keyword, and it can only take the values true or false.

Example:

val isKotlinFun: Boolean = true

val isFishTasty: Boolean = false

println(isKotlinFun) // Outputs: true

println(isFishTasty) // Outputs: falseExplanation:

isKotlinFunis set to true.isFishTastyis set to false.

Kotlin is Smart Enough to Detect Boolean Types

Just like other data types in Kotlin, you do not need to specify the type explicitly. Kotlin automatically understands that the values are Boolean.

Example:

val isKotlinFun = true

val isFishTasty = false

println(isKotlinFun) // Outputs: true

println(isFishTasty) // Outputs: falseWhy does this work?

- Kotlin automatically detects that

trueandfalseare Boolean values. - There is no need to specify

Booleanexplicitly.

Boolean Values in Conditional Statements

Boolean values are mostly used in conditional statements (like if statements), which

you will learn more about in a later chapter.

Example: Using Boolean in an If-Else Condition

val isSunny = true

if (isSunny) {

println("Let's go outside!")

} else {

println("Better stay indoors!")

}Output:

Let's go outside!Explanation:

- The condition inside

ifis true, so it prints"Let's go outside!". - If

isSunnywas false, it would print"Better stay indoors!".

Boolean Comparisons

Booleans are often used to compare values in Kotlin.

Example:

val x = 10

val y = 20

println(x > y) // Outputs: false

println(x < y) // Outputs: trueExplanation:

x > ychecks if10is greater than20, which is false.x < ychecks if10is less than20, which is true.

This unit covers conditional statements in Kotlin, including if..else and when expressions.

Kotlin Conditions and If..Else

Kotlin supports the usual logical conditions from mathematics:

- Less than:

a < b - Less than or equal to:

a <= b - Greater than:

a > b - Greater than or equal to:

a >= b - Equal to:

a == b - Not Equal to:

a != b

You can use these conditions to perform different actions based on decisions.

Kotlin provides the following conditionals:

- if: Executes a block of code if a specified condition is true.

- else: Executes a block of code if the same condition is false.

- else if: Checks a new condition if the first condition is false.

- when: Provides multiple alternative blocks of code.

Note: Unlike Java, if..else can be used as both a statement and an

expression in Kotlin.

Kotlin if Statement

The if statement executes a block of code if a condition is true.

Syntax:

if (condition) {

// Code to execute if the condition is true

}Example: Checking if 20 is greater than 18.

if (20 > 18) {

println("20 is greater than 18")

}You can also test variables:

val x = 20

val y = 18

if (x > y) {

println("x is greater than y")

}Explanation: The condition x > y is true, so "x is greater than y" is

printed.

Kotlin else Statement

The else statement executes a block of code when the if condition is false.

Syntax:

if (condition) {

// Code executed if condition is true

} else {

// Code executed if condition is false

}Example: Check the time and print a greeting.

val time = 20

if (time < 18) {

println("Good day.")

} else {

println("Good evening.")

}Output: "Good evening."

Explanation: The condition time < 18 is false, so the else block

runs.

Kotlin else if Statement

The else if statement allows multiple conditions to be checked.

Syntax:

if (condition1) {

// Code executed if condition1 is true

} else if (condition2) {

// Code executed if condition1 is false and condition2 is true

} else {

// Code executed if condition1 and condition2 are both false

}Example: Check different times of the day.

val time = 22

if (time < 10) {

println("Good morning.")

} else if (time < 20) {

println("Good day.")

} else {

println("Good evening.")

}Output: "Good evening."

Explanation: The first two conditions are false, so the else block executes.

Kotlin If..Else as an Expression

In Kotlin, if..else can also return a value and be assigned to a variable.

Example:

val time = 20

val greeting = if (time < 18) {

"Good day."

} else {

"Good evening."

}

println(greeting)Output: "Good evening."

Explanation: Since time is 20, the else block runs, assigning

"Good evening." to greeting.

Shorter If Expression (Ternary Alternative)

You can omit the curly braces { } when if has only one statement.

Example:

val time = 20

val greeting = if (time < 18) "Good day." else "Good evening."

println(greeting)Output: "Good evening."

Tip: This is similar to the ternary operator in Java.

Kotlin When Expression

Instead of writing multiple if..else expressions, Kotlin provides the when expression, which is much easier to read.

The when expression is used to select one of many possible code blocks to execute.

Example: Convert a Number to a Weekday

Use a number (1-7) to determine the corresponding day of the week.

val day = 4

val result = when (day) {

1 -> "Monday"

2 -> "Tuesday"

3 -> "Wednesday"

4 -> "Thursday"

5 -> "Friday"

6 -> "Saturday"

7 -> "Sunday"

else -> "Invalid day."

}

println(result)Output:

ThursdayExplanation:

- The value of

dayis 4. - when checks each branch to see if there is a match.

- Since

4 -> "Thursday"exists, "Thursday" is printed. - If no match is found, the

elsebranch runs.

How Kotlin When Works

The when expression works similarly to a switch statement in Java:

- The when variable (

day) is evaluated once. - Its value is compared with the values of each branch.

- Each branch contains a value, followed by an arrow (

->) and a result. - If a match is found, the corresponding block of code is executed.

- If no match is found, the else block runs.

Using When with Multiple Values

You can match multiple values in the same branch by separating them with commas.

val number = 2

val description = when (number) {

1, 2, 3 -> "Small number"

4, 5, 6 -> "Medium number"

else -> "Large number"

}

println(description)Output:

Small numberExplanation:

- Since

numberis 2, and1, 2, 3are grouped together, "Small number" is printed.

Using When with Ranges

You can check if a value is within a range using in.

val score = 85

val grade = when (score) {

in 90..100 -> "A"

in 80..89 -> "B"

in 70..79 -> "C"

in 60..69 -> "D"

else -> "F"

}

println("Grade: $grade")Output:

Grade: BExplanation:

- The value of

scoreis 85. - Since

85is in the range80..89, "B" is assigned tograde.

Using When as an Expression

You can use when to assign a value to a variable.

val age = 18

val category = when {

age < 13 -> "Child"

age in 13..19 -> "Teenager"

age in 20..64 -> "Adult"

else -> "Senior"

}

println("Category: $category")Output:

Category: TeenagerExplanation:

- The when statement works as an expression and assigns a value to

category. - Since

age = 18, the conditionage in 13..19is true, so "Teenager" is assigned.

Kotlin Loops

Loops allow us to execute a block of code multiple times, as long as a specified condition is met.

Loops are useful because they:

- Save time by avoiding repetitive code.

- Reduce the chance of errors in programs.

- Make code more efficient and readable.

Kotlin While Loop

The while loop executes a block of code as long as a specified condition is true.

Syntax:

while (condition) {

// Code block to execute

}In the example below, the loop will run as long as i is less than 5:

Example:

var i = 0

while (i < 5) {

println(i)

i++

}Output:

0

1

2

3

4Note: Always make sure to increase the loop variable (i++), otherwise, the loop will

run indefinitely.

Kotlin Do..While Loop

The do..while loop is a variation of the while loop.

It will execute the code block at least once before checking the condition, and then repeat the loop as long as the condition remains true.

Syntax:

do {

// Code block to execute

} while (condition)In the example below, the loop will run at least once before checking the condition:

Example:

var i = 0

do {

println(i)

i++

} while (i < 5)Output:

0

1

2

3

4Note: Like the while loop, always ensure to increase the loop variable (i++)

to prevent infinite loops.

Kotlin Break Statement

The break statement is used to exit a loop immediately when a certain condition is met.

In the example below, the loop will stop completely when i equals 4:

Example:

var i = 0

while (i < 10) {

println(i)

i++

if (i == 4) {

break

}

}Output:

0

1

2

3Explanation:

- The loop starts at

i = 0and runs whilei < 10. - Once

i == 4, the break statement is executed, and the loop stops.

Kotlin Continue Statement

The continue statement skips the current iteration of the loop when a condition is met, but continues with the next iteration.

In the example below, the number 4 is skipped:

Example:

var i = 0

while (i < 10) {

if (i == 4) {

i++

continue

}

println(i)

i++

}Output:

0

1

2

3

5

6

7

8

9Explanation:

- The loop runs from

i = 0toi = 9. - When

i == 4, the continue statement skips printing 4 and moves to the next iteration. - As a result, 4 is not printed.

This unit covers **Kotlin Arrays**, their operations, and how to manipulate them.

Kotlin Arrays

Arrays are used to store multiple values in a single variable instead of creating separate variables for each value.

To create an array, use the arrayOf() function and place the values inside it:

Example:

val cars = arrayOf("Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda")Accessing Elements in an Array

You can access an array element by referring to its index number inside square brackets.

Example:

val cars = arrayOf("Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda")

println(cars[0]) // Outputs: VolvoNote: Like Strings, array indexes start from 0: [0] is the first

element, [1] is the second, and so on.

Changing an Array Element

To modify a specific element in an array, assign a new value using the index number:

Example:

val cars = arrayOf("Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda")

cars[0] = "Opel"

println(cars[0]) // Outputs: OpelFinding the Length of an Array

To find out how many elements an array contains, use the size property:

Example:

val cars = arrayOf("Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda")

println(cars.size) // Outputs: 4Checking if an Element Exists

You can use the in operator to check whether an element exists in an array.

Example:

val cars = arrayOf("Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda")

if ("Volvo" in cars) {

println("It exists!")

} else {

println("It does not exist.")

}Output:

It exists!Looping Through an Array

When working with arrays, you often need to loop through all elements. You can use the for loop to iterate through an array.

Example:

val cars = arrayOf("Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda")

for (x in cars) {

println(x)

}Output:

Volvo

BMW

Ford

MazdaKotlin For Loop

Often when working with arrays, you need to loop through all elements.

To loop through array elements, use the for loop together with the in operator.

Looping Through an Array

In this example, we loop through a list of car brands and print each element:

Example:

val cars = arrayOf("Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda")

for (x in cars) {

println(x)

}Output:

Volvo

BMW

Ford

MazdaYou can loop through all kinds of arrays. In the example above, we used an array of strings.

Looping Through an Array of Numbers

In this example, we loop through an array of integers:

Example:

val nums = arrayOf(1, 5, 10, 15, 20)

for (x in nums) {

println(x)

}Output:

1

5

10

15

20Traditional For Loop in Kotlin

Unlike Java and other programming languages, there is **no** traditional for loop in Kotlin.

In Kotlin, the for loop is used to loop through arrays, ranges, and other things that contain a countable number of values.

Kotlin Ranges

With the for loop, you can also create ranges of values using the .. operator.

Printing a Range of Characters

You can loop through the entire alphabet or any subset of characters using a range.

Example:

for (chars in 'a'..'x') {

println(chars)

}Output:

a

b

c

...

xNote: The first and last value are included in the range.

Printing a Range of Numbers

You can also create ranges of numbers:

Example:

for (nums in 5..15) {

println(nums)

}Output:

5

6

7

...

15Checking if a Value Exists in a Range

You can use the in operator to check if a value exists in an array or range.

Example 1: Checking in a Numeric Array

val nums = arrayOf(2, 4, 6, 8)

if (2 in nums) {

println("It exists!")

} else {

println("It does not exist.")

}Output:

It exists!Example 2: Checking in a String Array

val cars = arrayOf("Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda")

if ("Volvo" in cars) {

println("It exists!")

} else {

println("It does not exist.")

}Output:

It exists!Breaking a Range Loop

Use the break keyword to stop a loop when a specific condition is met.

Example: Stop the loop when nums is equal to 10.

for (nums in 5..15) {

if (nums == 10) {

break

}

println(nums)

}Output:

5

6

7

8

9Skipping a Value in a Range Loop

Use the continue keyword to skip a specific value and proceed to the next iteration.

Example: Skip the value of 10 in the loop and continue with the next iteration.

for (nums in 5..15) {

if (nums == 10) {

continue

}

println(nums)

}Output:

5

6

7

8

9

11

12

...

15🎉 Now that you understand **Kotlin Ranges**, let's move on to **Kotlin Functions** in the next section!

Kotlin Functions

A function is a block of code that runs only when it is called.

You can pass data, known as parameters, into a function.

Functions are used to perform certain actions, and they are also known as methods.

Predefined Functions

You have already been using functions in Kotlin! The println() function is an example of a predefined function that prints text to the screen.

Example:

fun main() {

println("Hello World")

}Create Your Own Functions

To create a function, use the fun keyword followed by the function name and parentheses ().

Example: Creating a function named "myFunction"

fun myFunction() {

println("I just got executed!")

}Calling a Function

To execute a function, simply call it by writing its name followed by parentheses ().

Example:

fun main() {

myFunction() // Call myFunction

}

// Outputs:

// I just got executed!A function can be called multiple times.

Example:

fun main() {

myFunction()

myFunction()

myFunction()

}

// Outputs:

// I just got executed!

// I just got executed!

// I just got executed!Function Parameters

Functions can take input values known as parameters.

Parameters are defined inside the parentheses, and their types must be specified.

Example: Function with a single parameter

fun myFunction(fname: String) {

println(fname + " Doe")

}

fun main() {

myFunction("John")

myFunction("Jane")

myFunction("George")

}

// Outputs:

// John Doe

// Jane Doe

// George DoeMultiple Parameters

You can pass multiple parameters, separated by commas.

Example:

fun myFunction(fname: String, age: Int) {

println(fname + " is " + age)

}

fun main() {

myFunction("John", 35)

myFunction("Jane", 32)

myFunction("George", 15)

}

// Outputs:

// John is 35

// Jane is 32

// George is 15Note: The number of arguments must match the number of parameters.

Return Values

Functions can also return values instead of just printing them.

To return a value, use the return keyword and specify the return type.

Example: Function with return value

fun myFunction(x: Int): Int {

return (x + 5)

}

fun main() {

var result = myFunction(3)

println(result)

}

// Outputs:

// 8Example: Function with multiple parameters and return value

fun myFunction(x: Int, y: Int): Int {

return (x + y)

}

fun main() {

var result = myFunction(3, 5)

println(result)

}

// Outputs:

// 8Shorter Syntax for Return Values

Kotlin allows a shorter syntax by using = instead of return.

Example:

fun myFunction(x: Int, y: Int) = x + y

fun main() {

var result = myFunction(3, 5)

println(result)

}

// Outputs:

// 8Welcome to **Unit 5: Object-Oriented Programming (OOP)**. In this unit, we will learn about OOP principles in Kotlin, including classes, objects, inheritance, polymorphism, and more.

Kotlin - What is OOP?

OOP stands for Object-Oriented Programming.

Procedural programming focuses on writing procedures or methods that perform operations on data, whereas object-oriented programming focuses on creating objects that contain both data and methods.

Advantages of OOP over Procedural Programming:

- ✅ OOP is faster and easier to execute.

- ✅ OOP provides a clear structure for programs.

- ✅ OOP helps keep the Kotlin code DRY (Don't Repeat Yourself), making it easier to maintain, modify, and debug.

- ✅ OOP makes it possible to create reusable applications with less code and shorter development time.

Tip:

The DRY principle aims to reduce the repetition of code. It suggests extracting common functionality and reusing it instead of duplicating the same code multiple times.

Kotlin - What are Classes and Objects?

Classes and objects are the two main components of object-oriented programming.

Class vs Objects - Example:

A class is a template for objects, while an object is an instance of a class.

Illustration:

| Class | Objects |

|---|---|

| Fruit | 🍎 Apple, 🍌 Banana, 🥭 Mango |

| Car | 🚗 Volvo, 🚙 Audi, 🚘 Toyota |

When individual objects are created, they inherit all the variables and methods from the class.

Kotlin Classes/Objects

Everything in Kotlin is associated with classes and objects, along with their properties and functions. For example, in real life, a car is an object. A car has properties such as brand, weight, and color, and functions such as drive and brake.

A class is like an object constructor or a "blueprint" for creating objects.

Create a Class

To create a class, use the class keyword, followed by the name of the class:

Example

class Car {

var brand = ""

var model = ""

var year = 0

}A property is essentially a variable that belongs to the class.

Good to Know:

It is considered best practice to start the name of a class with an uppercase letter for better readability.

Create an Object

Now we can use the Car class to create objects.

In the example below, we create an object of Car called c1, and then access its properties using the dot syntax (.):

Example

// Create a c1 object of the Car class

val c1 = Car()

// Access the properties and add values

c1.brand = "Ford"

c1.model = "Mustang"

c1.year = 1969

println(c1.brand) // Outputs Ford

println(c1.model) // Outputs Mustang

println(c1.year) // Outputs 1969Multiple Objects

You can create multiple objects of a single class:

Example

val c1 = Car()

c1.brand = "Ford"

c1.model = "Mustang"

c1.year = 1969

val c2 = Car()

c2.brand = "BMW"

c2.model = "X5"

c2.year = 1999

println(c1.brand) // Ford

println(c2.brand) // BMWKotlin Constructor

In the previous chapter, we created an object of a class, and specified the properties inside the class like this:

Example

class Car {

var brand = ""

var model = ""

var year = 0

}

fun main() {

val c1 = Car()

c1.brand = "Ford"

c1.model = "Mustang"

c1.year = 1969

}In Kotlin, there's a faster way of doing this, by using a constructor.

What is a Constructor?

A constructor is like a special function, and it is defined by using two parentheses () after the class name.

You can specify the properties inside the parentheses (just like passing parameters into a function).

The constructor will initialize the properties when you create an object of a class.

Example

class Car(var brand: String, var model: String, var year: Int)

fun main() {

val c1 = Car("Ford", "Mustang", 1969)

}Now it's even easier to specify multiple objects of the same class:

Example

class Car(var brand: String, var model: String, var year: Int)

fun main() {

val c1 = Car("Ford", "Mustang", 1969)

val c2 = Car("BMW", "X5", 1999)

val c3 = Car("Tesla", "Model S", 2020)

println(c1.brand) // Ford

println(c2.brand) // BMW

println(c3.brand) // Tesla

}Kotlin Class Functions

You can also use functions inside a class to perform certain actions.

Example

Create a drive() function inside the Car class and call it:

class Car(var brand: String, var model: String, var year: Int) {

// Class function

fun drive() {

println("Wrooom!")

}

}

fun main() {

val c1 = Car("Ford", "Mustang", 1969)

// Call the function

c1.drive()

}Tip: When a function is declared inside a class, it is known as a class function, or member function.

Note: When an object of the class is created, it has access to all of the class functions.

Class Function Parameters

Just like with regular functions, you can pass parameters to a class function.

Example

Create two functions: drive() and speed(), and pass parameters to the speed() function:

class Car(var brand: String, var model: String, var year: Int) {

// Class function

fun drive() {

println("Wrooom!")

}

// Class function with parameters

fun speed(maxSpeed: Int) {

println("Max speed is: " + maxSpeed)

}

}

fun main() {

val c1 = Car("Ford", "Mustang", 1969)

// Call the functions

c1.drive()

c1.speed(200)

}🎉 Now, we can add actions (functions) inside a class, making our objects even more powerful!

Kotlin Inheritance (Subclass and Superclass)

In Kotlin, it is possible to inherit class properties and functions from one class to another. We group the inheritance concept into two categories:

- Subclass (child) - the class that inherits from another class

- Superclass (parent) - the class being inherited from

Example

MyChildClass (subclass) inherits the properties from the MyParentClass class (superclass):

// Superclass (Parent)

open class MyParentClass {

val x = 5

}

// Subclass (Child)

class MyChildClass: MyParentClass() {

fun myFunction() {

println(x) // x is now inherited from the superclass

}

}

// Create an object of MyChildClass and call myFunction

fun main() {

val myObj = MyChildClass()

myObj.myFunction()

}Example Explained

- Use the open keyword in front of the superclass (parent), to allow other classes to inherit from it.

- To inherit from a class, specify the name of the subclass, followed by a colon (:), and then the name of the superclass.

Why And When To Use Inheritance?

Inheritance is useful for code reusability: reuse properties and functions of an existing class when you create a new class.